The Russians want to be paid, the Ukrainians want some combination of higher transit fees and lower prices, and the Europeans just want assurances that the gas will be delivered. In an EPRINC assessment published in March 2009, we concluded that Gazprom, as a price-taker, had incurred substantial losses from the low oil price environment and recurring gas disputes with Ukraine, thereby, highlighting that dependence goes both ways – Russia needs the European market as much as the latter needs Russian gas. Furthermore, we concluded that Ukraine could lose considerable economic leverage if Russia built either the Nord Stream or South Stream pipelines. While Russia is determined to charge ahead with building both pipelines, it is suffering from declining revenues from lower sales into Europe. Unless the Ukrainian transit issue is resolved, we are likely to see another cycle of payment disputes.

All three sides have a lot to gain through a long term resolution of the transit conflict, so why is it so difficult to obtain a stable agreement? In many respects the ongoing dispute over Russian gas deliveries represents a three party confrontation in which each party brings a unique, but constantly changing risk profile, and both the Russians and Europeans are seeking strategies for the other party to do more to get the Ukrainians to cooperate. However, a broad range of interests in Ukraine are facing severe economic and political pressures, and all of these stakeholders are well aware that Ukraine is the transit point for over 80 percent of Russian access to the European market. Kyiv remains in a position to extract higher fees or lower gas prices (economic rents) by diverting transit gas to domestic uses. While new pipelines are likely to diminish the importance of the Ukrainian transportation corridor, this traditional transit route will remain important when European gas demand recovers.

Although the Russians are actively pursuing alternative delivery routes to their European customers, for the time being, they are stuck with the Ukrainian transit corridor. The Russians can deny the gas to the Ukrainians, but all the parties involved also know that such cutoffs will result in reduced or no gas flow to Europe and at the same time further damage Russia’s reputation as a reliable supplier. Furthermore, conditions in the world gas market may now pose additional risks to the Russians.

Although oil prices have recovered somewhat from their collapse in late 2008 and early 2009, we are likely entering into a market where natural gas prices will remain relatively low, at least for an interim period. European gas demand has risen between April and June, however, the EU has reduced its take from Gazprom. Some Russian officials are divided on the reasons why this happened. While Russia’s Deputy Energy Minister, Sergei Kudryashov, argues that Gazprom’s strict pricing drove European buyers to other gas suppliers who have raised their market share in the EU by granting discounts, the company’s CEO, Alexander Medvedev, claimed that Europe reduced its purchase of Russian gas between October 2008 and March 2009 due to lower gas spot market prices, which were half the cost of the long-term contracts. For the Russians, the cost of cutting supplies to Ukraine are rising and the prospects for the Ukrainians to seek higher rents are improving, but the outcome remains uncertain as there is no clear path to resolution.

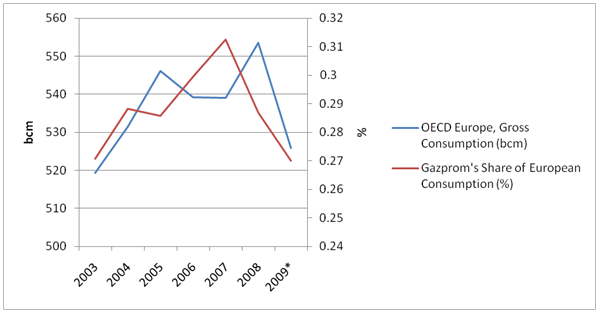

Against this background of a recurring dispute over transit arrangements, Gazprom is now facing one additional risk. As illustrated in Fig. 1, extensive discounting of gas to oil has been a feature of the U.S. gas markets, which may emerge into a longer term characteristic of world oil and gas markets. While EPRINC is not yet prepared to conclude that long term gas prices will discount to oil at much higher rates over the longer term, there is a growing consensus that world gas supplies are likely to increase substantially as producers gain more knowledge on producing natural gas from unconventional formations.

Figure 1. Henry Hub Natural Gas and WTI Crude Oil Front Month Futures Prices

Source: EIA, EPRINC calculations

The Current Transit Dispute

After Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin announced on June 8, 2009, that the supply of natural gas to Ukraine and Europe would be stopped at the end of June or in early July if Ukraine failed to pay for the gas stored underground in May, Kyiv promptly paid the full $647 million to Gazprom that day. However, both Gazprom and European officials know that Ukraine’s payment problems are not likely to end with the May payment. Russia’s demand that Ukraine should make advanced payments for gas supplies and fill its storage facilities, which requires $4 billion to purchase the 19.5 bcm of gas are unlikely to be realized since Ukrainian financial resources are limited. At a meeting of EU countries, European Commission President, José Manuel Barroso, warned on June 19, 2009, that a “new crisis could be weeks away, unless funds can be found.” Ukraine’s negotiations with the International Monetary Fund yielded a $3.3 billion loan to help cover its gas payment for July, which were conditioned on reforms of the gas sector.

The 23rd EU-Russia summit on May 22, 2009, held in the Russian Far East city of Khabarovsk, brought no solution to the transit problem as Russia refused to give any assurance to the Europeans, while President Dmitry Medvedev’s idea that the EU provide more credit to Ukraine to help with the transit costs met rejection from the Europeans. Meantime, Gazprom’s Alexey Miller noted that if Ukraine’s Naftogaz was unable to make gas prepayments in full, it would “get as much gas as [it] pays for [and] there [was] no question of cutoffs.” But since Ukraine and Russia have not developed a mutually-agreeable payment solution for gas purchases, and none of the three parties have made a bona fide effort to resolve the transit problem, future gas cutoffs are inevitable.

Russian analysts acknowledge the country’s increasingly weakening position and the value of the European market. According to the deputy head of the Russian Nanotekhnologii corporation and former Minister of Economy, Yakov Urinon, “the tougher the Russian position is, the likelier we are to lose the European market […] it is easy to lose the market, but to enter it is quite difficult and costly.” In fact, Russia’s risk profile is worsening as gas prices continue to fall and it is already in a far less advantageous position compared to last year. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), Norwegian gas and LNG from Qatar and Trinidad and Tobago have made substantial inroads into the European market share lost by Russia.

Changing Market Dynamics

The current energy reality in Europe summed up by Bernhard Reutersberg, CEO of the German E.ON Ruhrgas AG, that “the days of high growth rates for European gas consumption are surely over” carries significant implications for Russia’s future gas supplies and its resource-based economy.

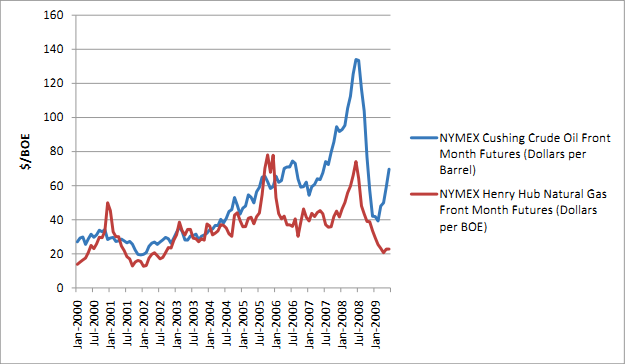

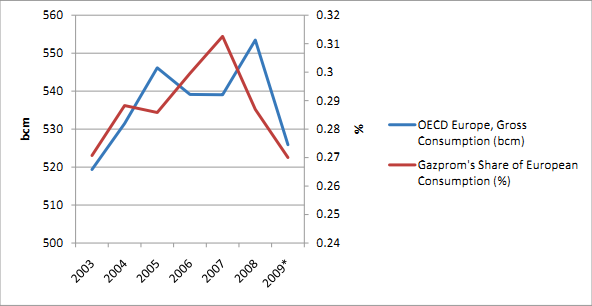

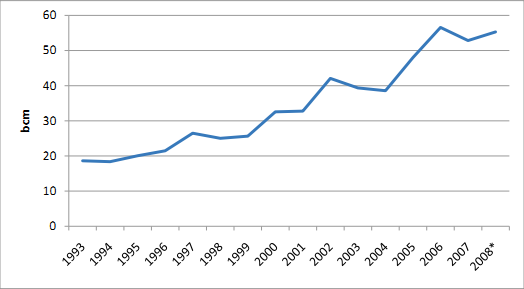

Figure 2. European Gas Consumption and Gazprom’s Share

Source: IEA Data, Gazprom Data, EPRINC calculations. Estimate for 2009.

Figure 2 suggests that Gazprom is a high-cost, marginal supplier to Europe. Europeans appear to be reducing gas consumption in large part by cutting imports from Gazprom. Gazprom’s estimated gas sales to Europe in 2009 will be significantly lower in 2009 than in 2008 and Gazprom’s market share will also decline as Europeans reduce consumption and find alternative sources of gas such as LNG.

Gazprom is staying with its historic pricing formula which links gas prices to oil prices at a fixed ratio, generally adjusted with a 6 to 9 month lag. Since oil prices have declined well off their 2008 highs, Gazprom will adjust its pricing accordingly. However, this adjustment may not be low enough to protect Gazprom’s position in the European market given the growing availability of low cost LNG. For now, gas has decoupled from its historic relationship to oil.

Gazprom’s production declined 34 percent year over year. Faced with the declining gas prices and demand, Gazprom is likely to be pressed to redo some of the established long-term contracts, particularly with the emergence of alternative sources of gas. In fact, Russia’s unresolved transit issues and Western concerns about rising dependence on Russian gas have encouraged the Europeans to both look into alternative gas suppliers and opportunities for accessing the growing world LNG market. LNG imports to Europe have risen to 44.8 million tons in 2008 compared to 2007 imports of 44.1 million tons. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) Europe has been buying more LNG in 2008-09, with an expected rise in shipments of more than 40% in July and August of 2009. Because European gas demand is seasonal, LNG gas imports have peaked in the wintertime and were at the lowest in the summer. As more LNG spot cargo contracts that allow for destination flexibility reach the market, Europeans may have opportunities to diversify away from Russian natural gas, at least in the near term.

Figure 3. LNG Imports to Europe

Sources: EIA, BP Statistical Review (2007& 2008 est.)

Current European LNG terminals can import 95 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year and six new terminals that are being built could increase this annual import capacity by 70 bcm. Although declining gas prices and demand are slowing the build-up of new LNG supplies, LNG’s potential to offset the pipeline gas carry a significant appeal to the Europeans. As many industry analysts forecast a growing competition between LNG and pipeline gas, LNG supplies from countries like Qatar are likely to saturate the European markets once the latter rebound from the current economic slump.

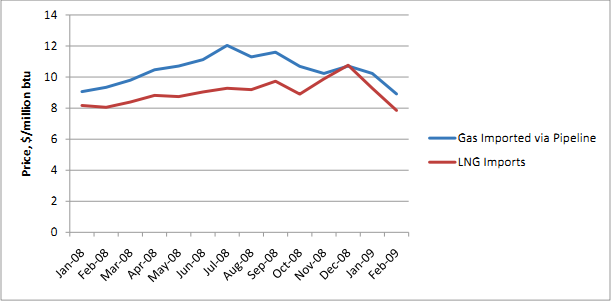

A fixed ratio between natural gas and oil prices, with a 6 to 9 month lag, has been the traditional method of setting natural gas prices in European contracts with Gazprom. However, the transit dispute combined with the growing availability (and lower prices) of spot LNG are giving the Europeans opportunities to not only reduce gas purchases from Russia, but the cheap gas is also undermining confidence in the historic pricing index for European gas sales from Gazprom. As illustrated in Fig. 4, LNG import prices into Europe have dropped markedly since late 2008. In a market in which natural gas prices are lower than oil prices, the incentives to move towards lower priced spot LNG cargos are very high.

Figure 4. Natural Gas Import Prices to Europe

Source: IEA, EPRINC calculations

Although the EU can take advantage of growing supplies of spot LNG cargos in the near term, there remains a strong desire for longer term diversification of supply. As part of its energy diversification policy, the EU has recently moved ahead with the Nabucco project by signing an agreement in early May, 2009 with Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey and Egypt to revive the pipeline talks, including a separate EU-Turkey deal to clear a way for this line. However, until it becomes clear who will supply the gas, who will buy it and how it will be financed, Nabucco is unlikely to go forward. In addition, regulatory uncertainties in the EU may complicate Nabucco’s implementation as the pipeline will go through “five different IEA European countries [and] various factors must be individually negotiated, including the rate of return, third-party-access regime, approvals process, length of time to approval and the roles of the national and EC authorities.”

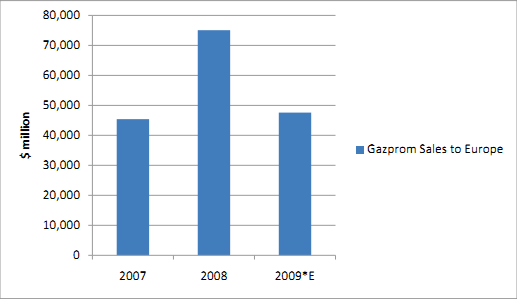

Gazprom’s Current Situation

Low gas prices have already contributed to Gazprom’s declining output, which fell by over a quarter in April 2009 to the lowest level in a decade and is likely to shrink further if demand remains modest. Recession-afflicted European economies are likely to reduce demand by nearly 10 per cent this year. Gazprom expects that European consumers will pay around $260 per thousand cubic meters (tcm), which is down from its February 2009 forecast of $280 per tcm. These factors combined will lower Gazprom’s European export revenues by about 37% in 2009 over 2008.

Figure 5. Gazprom Revenues from Sales to Europe

Source: UniCredit, May 15, 2009.

While oil prices have recovered, U.S. gas and some LNG prices have not. In addition, there is growing evidence that Ukraine and the EU consumer states are waiting for gas prices to fall further, limiting current consumption of more expensive gas and instead taking more gas from storage. Russia, however, is pushing for Ukraine to buy its gas now at a higher price. A fundamental question both European consumers and Gazprom must now confront is whether the recent decoupling of the traditional ratio of gas values to oil is a near or long term development.

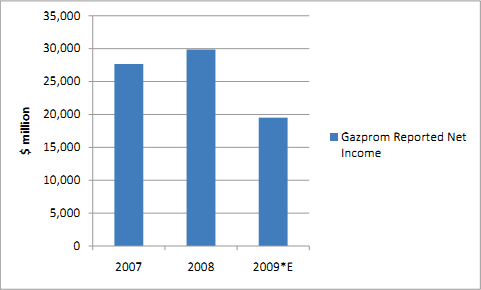

According to the Russian Finance Ministry’s projected federal budget for 2009, the country’s revenue from oil and gas amounts to RUB 2,351 billion of its total revenue of RUB 7,465 billion. The Finance Ministry projects that oil and gas revenue will be kept at RUB 2,348 billion of the total budget of RUB 8,089 billion in 2010. On June 10, 2009, the deputy Finance Minister of Russia, Oksana Sergienko, announced that the country’s budget deficit will amount to 9.3-9.9% of GDP, if oil averages $45/bbl for 2009. Although Russian crude oil has recently been trading at around $60-$70/bbl, the Finance Ministry remains cautious about making revenue projections. Since Gazprom’s profits are responsible for about 20% to Russia’s annual budget, falling demand and declining prices could restrict government revenues for years to come.

Figure 6. Gazprom Reported Net Income

Source: UniCredit, May 15, 2009.

According to Gazprom’s deputy chairman, Alexander Ananenkov, “gas production could fall between 450 and 510 bcm compared with 550 bcm produced last year.” Another senior Gazprom official said in April 2009 that the company’s capital expenditure will be “much lower” this year than the budgeted $27.55 billion, approved in December 2008, while gas output faced a potential cut by over 10 per cent.

Although Gazprom pushed for the funding and development of key projects such as the Shtokman gas field and those in the Yamal peninsula despite its financial struggles, the company is now considering a delay of these projects due to weak gas demand. Gazprom’s budget problems are compounded by its commitment to buy Central Asian gas at prices much higher than current world prices and being forced to sell this gas at a loss although the company has cut purchases of Central Asian gas by almost twofold in the second quarter of 2009.

Ukraine’s Position

The global recession severely hit Ukraine’s economy. President Viktor Yushchenko announced on June 10, 2009, that the economy shrank by 25% in the first quarter of this year, noting that it is getting worse. Faced with a potential default on its future gas payments, Ukrainian authorities began discussing various gas payment options, along with reducing gas consumption. A source from the Ukrainian President’s Secretariat noted that “the most suitable option whereby there is the least danger for payment arrears would be paying for gas when purchasing it, however, this option is not currently in place.” A Ukrainian government source stressed that the continuing negotiations between Naftogaz and Gazprom would yield a payment option. Ukrainians further argue that the country’s ability to come to an agreement with Russia on a payment option will depend on whether both countries can agree on Kyiv’s efforts to reduce gas consumption by about 30-40% in 2009, that is, if it can go to a contract minimum, without being fined. Recent discussions between Ukraine and the U.S. on investments to move forward the Ukrainian government energy efficiency program during Vice President Joe Biden’s visit to Kyiv is another step towards lowering its energy dependence on Russia.

Historically, natural gas deliveries to the EU have been delivered through both direct transmission from Russia, as well as from storage facilities in Ukraine, particularly in periods of peak demand. Both the transmission and storage of natural gas have been managed by the Ukrainians, most recently by Natfogaz, a government-owned Ukrainian energy company. However, many of the storage sites have yet to be filled largely because a dispute has arisen over how the purchase of stored gas should be financed, i.e., who should pay for it. The EU recently indicated that it would be ready to pay Kyiv for use of underutilized gas storage facilities, but this issue is far from resolved.

Given the current low gas price environment, if the transit and payment problems persist, both Ukraine and Russia will be much worse off, as the EU will continue to move towards take or pay contract minimums with Russia, while pushing for more alternatives such as LNG supplies. Until all three parties come to an agreement on gas transit fees and a stable payment arrangement with the Ukrainians, we will likely see several reruns of the European gas drama.